SELF-CARE IN TIMES OF GENOCIDE

By Dr Leila Dehghan-Zaklaki

For the last nine months, we’ve been bombarded with horrific images and stories on our phones. It’s tough to keep going when you’re constantly seeing human and animal suffering, starvation, and killings. The daily exposure to such intense trauma can lead to emotional numbness or overwhelming despair, making it hard to focus on anything else.

For those of us in the health and wellness industry, this brings up a big question: What does self-care mean during times like these? As a Muslim Middle Easterner, I used to think self-care during a genocide seemed ridiculous—until I came across Audre Lorde’s words: “caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.” This highlights the radical nature of self-care in the face of systemic oppression. It reminds us that maintaining our well-being is essential to sustaining our resistance and supporting those who are suffering.

But what does self-care in times of genocide mean?

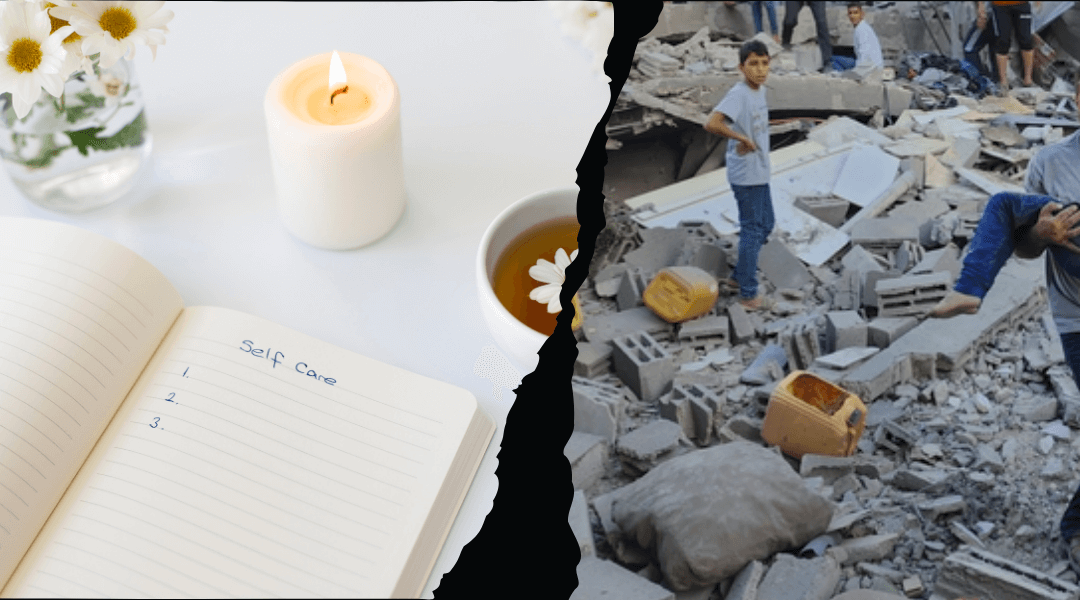

The media often portrays self-care as meditating, buying perfumed candles, or going on retreats—all attempts to disconnect from the “chaos” around us while solely tending to our own needs. We’ve all heard this sort of advice, and some of us have even shared it with clients. But let’s be real—that’s not what true self-care is about, definitely not for those of us from marginalised communities who have been facing decades of injustice and have a visceral understanding of the current genocide. A yoga retreat would do little good when you close your eyes and see images of maimed children, knowing there is no end in sight and nothing is being done to address the systemic issues that perpetuate this genocide.

This overly individualistic approach to self-care is a leftover from colonisation. Dr. Rocio Rosales Meza suggests decolonising mental health; she believes that self-care should go beyond just focusing on ourselves; it should include collective healing and resilience. She argues that practices rooted in indigenous traditions, such as communal gatherings and rituals, offer a more holistic approach to healing. These practices emphasise the importance of community and interconnectedness, challenging the isolated self-care models promoted by mainstream culture.

In times of televised genocide, self-care means caring for your own well-being while also engaging with the broader issues at play, and also mobilising to fight the injustice.

It’s about recognising how interconnected we all are and how injustices affect us all, how none of us is truly free and safe until we all are free and safe. Instead of isolating ourselves, true self-care means standing in solidarity with those affected by the current genocide. It means advocating for their liberation and justice. It means addressing the systemic problems that have led to this genocide and perpetuate the atrocities. As Martin Luther King Jr. stated, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” Personal well-being needs to be linked with social activism.

For marginalised communities that are displaced and uprooted, self-care also involves reconnecting with our racial identity. It’s about finding strength in our communities, sharing our stories, and feeling seen and understood. This sense of belonging is crucial, so crucial that the powers in charge always try to isolate us. Cultural practices, such as traditional dances, storytelling, and communal meals, can serve as powerful acts of resistance and sources of strength.

There’s no one-size-fits-all approach to self-care, and I, for one, don’t like it when others dictate how I should look after my mental and spiritual health when my people are being killed. So I hope you trust your instincts and do what feels right for you. With that said, don’t underestimate the power of community. Communities provide support, amplify individual efforts, and keep hope alive for a better future. They offer a sense of solidarity and shared purpose that can be incredibly grounding in turbulent times.

As the African proverb goes, “If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.”